Unbeaten, Unstoppable, Uncrowned

An Oral History of the 1994 Penn State Football Team

Part 1: We trace the ’94 team back to its roots, following the recruiting classes of 1990 and ’91 as they mature from talented prospects into proven leaders who will provide the foundation for greatness.

Chapter 1: Building the Foundation

In the winter of 1990, Joe Paterno’s staff inked a 16-player recruiting class, led by stud tight end prospect Kyle Brady and featuring a trio of quarterbacks. One of them was Kerry Collins, whom one Philadelphia newspaper described as “the biggest and strongest of the bunch… has been mentioned as a possible tight end candidate.”

PAUL “BUCKY” GREELEY: Growing up a Pennsylvania kid, the opportunity to even be recruited by Penn State, it’s almost like that was a win. For family members, friends, people in my high school, when Penn State was recruiting me, that was the accomplishment.

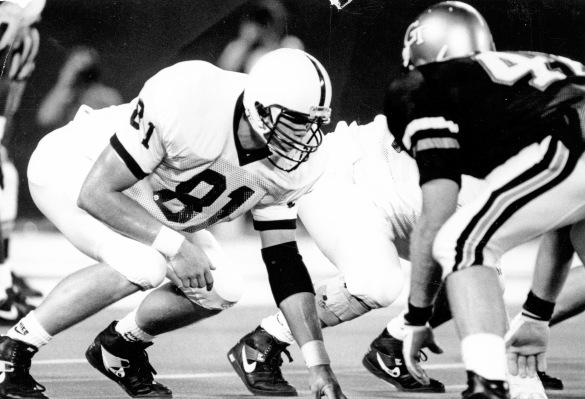

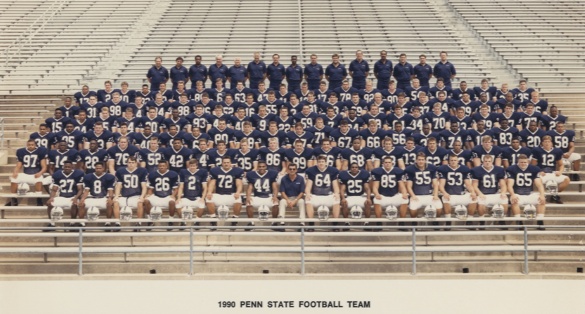

KYLE BRADY: When we first got there in 1990, most of us redshirted. Our class was a small one—I think we only had 16 guys—but we had a couple of quality guys: Kerry, myself, Bucky Greeley, Brian Gelzheiser, Phil Yeboah-Kodie.

KERRY COLLINS: Certainly Kyle was a big-name recruit, and there were a couple of other guys. I don’t know what the ranking was, but I got the feeling that everyone was excited about our class.

FRAN GANTER: We knew Kerry was going to be something special.

COLLINS: Initially, there were four or five of us—John Sacca, Danny White, Craig Fayak, who at the time was a quarterback—but I don’t remember that scaring me too much. I felt like Penn State was the best place for me. I had an assurance that I was gonna be a quarterback, and I took them at their word. Even when I was there, I would kind of tease Billy Kenney, who recruited me, “Hey, you guys aren’t going to move me.”

GREELEY: I played against Kerry my senior year, and he was my quarterback at Big 33, and there was no doubt he was going to be the quarterback. He had the confidence, the raw talent, the leadership ability. I look at a lot of the stuff that was written back then… we never had those doubts.

–––

Not every member of that class was a sure thing.

VINCENT STEWART: I didn’t play football until tenth grade. I’m this 6-foot-4, 280-pound guy out of Long Island that nobody knows about. After a lot of pushing from my coaches, I ended up at Penn State camp going into 11th grade. Joe Sarra was in charge of the defensive tackles, and he was the guy who spotted me, inspired me, and ultimately fought for me to get my scholarship. From that day on, by hook or by crook, I was going to Penn State…

On my visit, I sat with Coach Paterno, and the first and only thing he talked about was school. I talked to a lot of other coaches, they talked about playing time and all that, but none of them really talked about school. I knew something was different when Coach Paterno looked me in the eye and said, “Just give me all you can. I don’t care if you come here and don’t play, you’re going to graduate.” I had four other recruiting trips scheduled, and I cancelled all of them.

–––

The group that would form the core of the 1994 team drew heavily from the recruiting classes of 1990 and ’91. There were a handful of exceptions, including a pair of 1989 high school graduates. One was defensive tackle Chris Mazyck, who tells his story in Chapter 3; the other was cornerback Marlon Forbes.

MARLON FORBES: I came to Penn State as an ROTC student. I graduated in ’89, then went into the Navy right out of high school. I qualified for a program where you become a scholarship ROTC student at the school of your choice. I wanted to go to Penn State anyway, and this became a vehicle to get there. So in the fall of 1990, I walked on as a quarterback and wide receiver.

Once I got on the team, I took at look at the quarterbacks we had, and I was like, “You gotta be kidding me. Everybody’s good here.” The receivers? It was Dave Daniels, Terry Smith, O.J. McDuffy, Ricky Sayles… It seemed like we had everything. It might’ve been the second or third practice, and one of the coaches said “Hey, you ever play defensive back?” I was like, “Not really.” Next thing I know, I’m a scout team DB. Ron Dickerson said, “Come back next spring on defense,” and that was it.

–––

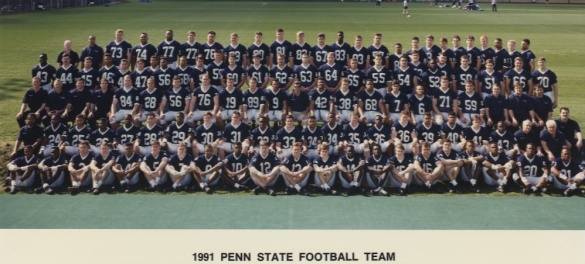

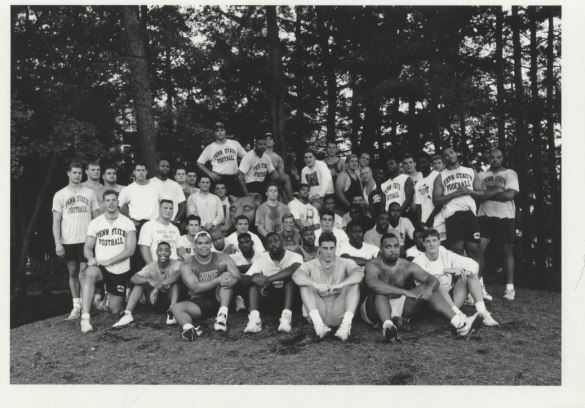

Forbes was understandably impressed by the Lions’ veteran skill players that fall; a year later, he and the rest of the Penn State squad would be wowed by an incoming freshman class that stands as arguably the greatest in Penn State history. Boasting nearly two dozen players, the ’91 recruiting class was particularly loaded with offensive linemen—Keith Conlin, Jeff Hartings, Andre Johnson, and Marco Rivera among them—and running backs. Analysts called it the top class in the nation. Who were those freshmen to disagree?

KEITH CONLIN: We were the No. 1 class in the country. We were Joe’s best recruiting class of all time. The running backs, the offensive linemen, everywhere, we were loaded.

MARCO RIVERA: Even before we got up to Penn State, we knew all these guys right away, from reading about them in the newspaper. We knew we had a good class.

GANTER: There were so many kids who were hard to get, and we worked hard to get them.

TONY PITTMAN: With those two classes, ’90 and ’91, it was like, “Wow, we’ve got a lot of talent coming in.” But you never know how that talent pans out.

BRADY: We had heard so much about that ’91 class. I was already starting to take those things with a grain of salt. Guys can be all-world in high school—you hear all these numbers about their speed and bench press—then they get there and it’s a different story. You never know what you’re going to get.

TODD ATKINS: A bunch of us—myself, Keith Conlin, Eric Clair, Mike Archie—we all played on the Pennsylvania Big 33 team, so quite a few of us knew each other coming into camp. It seemed like everybody kind of gelled.

BOBBY ENGRAM: It seemed uncommon at the time, how well we all got along.

CONLIN: I played with seven or eight guys in the Big 33 game, so we already had our little clique going. Plus, a lot of us were recruited by the same teams. I ended up living with Eric Clair for four of my five years there, and we first met on a visit to Florida State.

RIVERA: I remember I went on a recruiting trip to Syracuse, and I’m standing there with Andre Johnson—he’s a lineman from Long Island, I’m a lineman from Long Island—and I’m asking him, “Where do you think you’re going?” And he’s asking me… Next think you know, I commit to Penn State, he commits to Penn State. That’s how it happened with us.

MIKE ARCHIE: When I came in, you know who my host was? Kerry Collins. It was just a great time. Touring me around, showing me the campus, he really did feel like a brother. I remember meeting Keith Conlin and Marco Rivera and thinking, “Are these guys coming here? Because these guys are pretty big.”

COLLINS: The offensive linemen, it’s hard to see into the future with those guys—Jeff Hartings put on probably 70 pounds when he was there. Those guys had to grow into it. But you could see it. That class kind of carried themselves in a certain way. They knew they were good.

BRADY: Guys like Jeff Hartings and Marco Rivera, they were the ideal guys to come in as offensive linemen. You don’t want a guy to come in at 300 pounds with a bunch of baby fat. You want a guy who shows up maybe 260, athletic, maybe played basketball in high school, then you get them in the weight room and build them up from there. Their work ethic was tremendous, they had the smarts, they had the talent. You don’t know what the potential could be, but it could really be something.

GREELEY: When that class came in, they were loaded for bear. The expectation was, “We’re going to be good. How good? We want to be national champions.”

JEFF HARTINGS: I think with a Joe Paterno team, all of us went there for one reason. That was to win national titles.

KI-JANA CARTER: We were all close with each other, we had no egos, and we knew we had the No. 1 class coming in. We basically sat down and said, “We know what we’ve got here. Before we leave, we want to go undefeated and win a national championship.”

ARCHIE: When we first came in, we had a little meeting, and I believe it was Kerry who stood up and said, “There is no reason, by the time we get out of here, we shouldn’t be a national championship-caliber team.”

TOM BRADLEY: If you look at Penn State’s greatest teams, the seeds of those teams were probably built when those guys were freshmen. The ’82 team, it was the ’79 team going to the national championship game.

GREELEY: There were a lot of guys in both of those classes who could’ve gone to other schools and made contributions earlier, but we all saw the opportunity and bought into our goals at Penn State. I know I took it personally that every class up until that point, Joe used to say, “You’re either going to have an undefeated team or play for a national championship.” I was like, “I don’t want to be the class that breaks that streak.”

–––

A common feature on Joe Paterno’s championship-caliber teams was the presence of at least one transcendent running back. The ’91 class featured a half-dozen potential backfield stars: tailbacks Mike Archie, Ki-Jana Carter, J.T. Morris (who eventually transferred), and Stephen Pitts, along with Brian Milne and linebacker-turned-fullback Jon Wittman.

CARTER: I think Mike committed first, then Stephen, then myself.

ARCHIE: If memory serves, I was the last to come in.

STEPHEN PITTS: If I wasn’t the first of the three of us, I was at least the second. Ki-Jana kind of came on at the end, when some things fell apart with his recruiting at Ohio State.

CARTER: Me and Archie were on the same visit.

ARCHIE: I knew about Ki-Jana, and I knew about Stephen, and I knew about J.T. Morris. I was wondering if all these guys were gonna come in. But it was fun to meet them on the visits. You get to talking—Ki-Jana’s like, “You thinking about coming here?” I’m like, “I don’t know, are you thinking about coming here?”

CARTER: Wherever you go, there’s gonna be competition. From my standpoint, if I can play, I’m gonna play anywhere. That’s how I felt. I went where I was comfortable.

PITTS: My process was kind of slow. I wasn’t one of those guys that dreamed of playing in the NFL. I loved the game—that was it. I was going to college regardless. The way I made the final pick was, if there was no football, where would I want to go to school?

ARCHIE: When I heard all three of them were coming here, I made up my mind. “I said, I probably could go anywhere and play right away, but if I’m going to be the best I can be, I’m going to go with that group right there.” I wanted to come in and compete with those guys. I knew I was only going to get better.

BRIAN MILNE: I came in as a tailback, but on our very first lap around Holuba Hall, I looked at Mike Archie, Ki-Jana Carter, and Stephen Michael Pitts and said, “You know what? I think I’m gonna change to fullback. I might be fast, but I’m not that fast.” You just look at these guys, see them run, it was like, “Oooh, boy.” I knew right away the talent that was in the room.

Chapter 2: Hints of Greatness

No matter the talent in the ’90 and ’91 classes, Penn Stater under Paterno was a place where seniority mattered. The new arrivals found that out soon enough.

STEWART: Every senior class, every year, it’s their team. Joe never played young players right away; we all learned you had to wait your turn. Your résumé went out the window. Penn State was our family, and this was the hierarchy.

CONLIN: I understood, because I had an older brother play here. We had respect for the older guys, and a lot of those guys were really good: O.J., Mark D’Onofrio, Tony Sacca, Ricky Sayles, Troy Drayton, those guys humbled us real quick. We were here four or five days—it was still July, and we’d just started freshman camp—and they shaved all our heads. Joe was real upset about that. This was right before we had to get our student IDs; I look like Gomer Pyle from Full Metal Jacket. Ki-Jana still talks about how his never grew back.

ARCHIE: I think I managed to escape that, but when Ki-Jana got his head shaved, I think it became permanent (laughs).

–––

Hierarchy established, the youngsters got their revenge on the practice field. Few had a chance to wear the blue practice jerseys that signified the first-team players, but at the very least, they could make sure the guys in those blues jerseys knew their names.

GANTER: I remember so many times during the preseason, how anxious we were to get the freshman class in, time them, weigh them, and get them out there. A couple of kids, right away you just knew were going to be special.

FORBES: That freshman class in ’91, once we saw them in practice, certain guys just jumped out right away. It was like, “If they all pan out…”

RIVERA: We decided early in our careers that we were going to be a special group. When we started practicing against the upperclassmen, none of us were in the blue jerseys just yet, but it was very competitive.

CONLIN: Our scout team was deadly. Tuesdays and Wednesdays, that was our Super Bowl. We weren’t going to get punked. D’Onfrio says it to this day—his senior year, he’s practicing against Marco, Bucky, myself, Jeff, Andre, then he’s going through games and having fewer problems against other teams.

STEWART: Our practices were insane.

BRAD “SPIDER” CALDWELL: That scout team was phenomenal. Those freshmen were really tearing it up, even overshadowing some of our upperclassmen, making them look bad. That’s when they really shined.

ARCHIE: Normally you don’t like scout team, because you get busted up by the defense. But with Stephen and Ki-Jana and me on that scout team… I remember one day, Ki-Jana runs a play, he busts it for a big gain. Joe Sarra says, “Run it again.” Stephen Pitts gets in, runs it up the middle and busts the play wide open. Sarra comes in, “Run it again.” I come in, run it up the middle, bust the play wide open. Every time, we hit the hole and bust it open. Mark D’Onofrio and Keith Goganious are come over saying, “I don’t care what you do, when you get the ball on the next play, you better go down.” That’s when you know you command their respect.

GANTER: Sometimes at practice, you’d glance across from one field to the other, and you’d see Ki-Jana making a great run, Bobby making a great catch. Kyle was way ahead of the curve physically. You want to be fair to the upperclassmen, and you want to make sure the younger guys aren’t handed anything. But you can see their potential. You’re sitting in a staff meeting thinking, “They can help us right away.”

–––

Few of those first- and second-year players were called on during the ’91 season, an 11-2 campaign that ended with a Fiesta Bowl win over Tennessee and No. 3 ranking in the final polls. Another new class of recruits signed on in 1992, with decidedly less fanfare than its immediate predecessor.

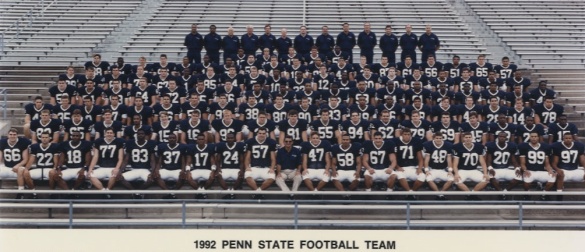

BRANDON NOBLE: On my visit, I was hanging out with Jeff Perry, Kerry Collins, Kyle Brady, Derek Bochna; we had a good time, but there was nothing spectacular about it. I slept on Jeff’s couch in Nittany Hall. There was nothing to do; we ended up at McDonald’s. At other places I visited, I was in a real nice hotel—there was some separation there. Here, I got a real taste of what it was going to be like in college. They weren’t trying to hide anything from me. It was very much, “This is who we are.” That struck a chord.

TERRY KILLENS: Our class was nowhere near as touted as ’91. I was a running back, and I knew what I was walking into, but with my competitive spirit, I thought maybe I could get a taste. We know how that turned out (laughs). I came up early before two-a-days, so I was able to see the locker room, with all the jerseys hung up. I saw No. 92 in my locker. I know running backs don’t wear 92. I found out pretty quick my days of being a running back were over.

FREDDIE SCOTT: I wasn’t as aware of the recruiting class prior to me. Going to high school in Detroit, I was more familiar with Michigan, and I was born in Miami, so I knew the Hurricanes. With Penn State, I really came in with a clean slate. Educationally, and with the guys I came in with, it’s where I felt most at home.

NOBLE: Our class was such a letdown after that ’91 class (laughs). Thank god we didn’t have the Internet back then. We didn’t have those big-name guys, but we didn’t need those big-name guys. We needed solid guys to come in and fill some gaps, and that’s what we did.

–––

It was no fault of those freshmen that their first season in Happy Valley was a hugely disappointing one for the team. Stuck in a sort of limbo before starting Big Ten play a year later, the ’92 Lions opened 5-0 before stumbling to a 7-5 record, finishing with a whimper in a 24-3 Blockbuster Bowl loss to Stanford.

CHUCK PENZENIK: My freshman year, even though we had a lot of really good players, we just didn’t live up to our potential. We freshman were like, “We didn’t come here for this.”

RIVERA: They had a great team, but they underachieved for some reason. I can’t put my finger on it, but they couldn’t get it done.

CONLIN: Some guys just didn’t want to be there.

KILLENS: Joe wasn’t happy, at all.

CARTER: When we got our butts kicked against Stanford, the younger guys saw that there was a lot of individualism. When you face adversity, some stuff comes out. We just said, “This is never going to happen to us. We’re never going to have that feeling again.”

RIVERA: We decided we didn’t want that. We wanted to be something special.

BRADY: There became this attitude of, “We’ve had enough of 7-5.”

PENZENIK: That next season, we started to get a feel for just how good we could be.

Chapter 3: Resilience Personified

The 1993 season marked the return of three players to the Nittany Lion roster who were sidelined in ’92. It was sheer coincidence that two of them were South Carolinians.

CHRIS MAZYCK: Being a Southern guy, my most memorable experience was probably that first day visiting in December—there’s a bunch of snow and slush on the ground. But Joe and the rest of the staff were straight up and down with me, and when Coach Paterno visited me in South Carolina, he won my over my parents and my grandmother…

My first season, ’89, the thing that sticks out is how family oriented it was. Leroy Thompson, Blair Thomas, Keith Goganious, Andre Collins, those guys kind of took me under their wings, showed me around. Not knowing me from a guy on the street, they were bringing me in, showing me the Penn State way.

ENGRAM: When I was a junior in high school, me and my cousin came to Penn State for camp. Our coach brought us up; he just wanted to show us something different. It was a summer day in June—what’s not to love about Happy Valley? We competed against a lot of the top guys from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Ohio, and then when I came up for my official visit, that sealed the deal. I knew they were going into the Big Ten, and I wanted that challenge.

MAZYCK: Bobby’s from South Carolina, too, so we had a relationship. We were the Southern kids on the block.

–––

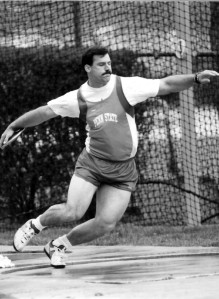

And then there was Brian Milne. In 1989, as a junior at Fort LeBoef High School near Erie, Milne had rushed for 2,419 yards, nearly breaking the state single-season record. He was also an Olympic hopeful in the discus. And then fate intervened.

MILNE: In March of my junior year, I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. They found a grapefruit-sized tumor on my heart. I had six months of chemotherapy and several serious surgeries: one that took out my tumor, one that took my spleen. I was given about a 50 percent chance to live. I didn’t play football my senior year.

BRADLEY: I recruited Brian out of high school. We had offered him, but when he got sick everybody backed off. Joe said, “Call him up. His offer’s good with me.”

MILNE: Coach Paterno called me in the hospital, and basically said, “Get better. Whether you play football or not, you’ll have a scholarship at Penn State.” I hung up the phone and said, “Huh.” When someone offers you that gift, you don’t look away, especially when you’re in the hospital and people are wondering if you’re going to live.

PITTMAN: I grew up not far from Brian, and we were in the same recruiting class, so I knew all about his story. Everyone had given up on him. Joe didn’t.

–––

Milne arrived on campus in remission but weakened, and sat out the ’91 season as he worked to regain his strength. Mazyck missed it as well: Home on spring break that March, he’d been shot six times by a convicted felon—the same man Mazyck had earlier warned off trying to date his younger sister. He was lucky not to have bled to death.

Then there was Engram, who played as a true freshman in ’91, but did so with the heaviest of hearts: His father had been killed in a car accident on the eve of the season. Almost exactly a year later, just before the start of the ’92 season, Engram was arrested for stealing stereo equipment from a State College apartment. For very different reasons, all three would miss the ’92 season.

ENGRAM: With my dad’s passing, and me making a dumb mistake a year later, that could’ve cost me everything. I wanted to leave, to be honest with you, but my mom wouldn’t let me. She said, “You’re going to stay there, do great things up there…”

I think sitting out in ’92 was the best thing that ever happened to me. It gave me a passion for the game I didn’t know I could have. It was the first time I hadn’t played football since I was 8 years old. I had played so much my freshman year, and I was slated to battle for a starting job… those fall Saturdays were probably some of the toughest times of my life. It hurt me, really bad. I said to myself, “When I have the opportunity to get back on the field, I’m going to make everybody remember me.”

MILNE: My first collegiate discus throw in ’92 qualified me for the Olympic trials—it was the leading throw in the world that year at that point. My whole goal was to go to the ’92 Olympics and win a medal. Unfortunately, two or three days after that throw, I had an emergency appendectomy. In my eyes, that kept me out of the Olympics…

My second day in the hospital, I asked the physical therapy people to bring in some weights. They looked at me like I had three heads, but for me, at that point, appendicitis was like a scratch.

MAZYCK: I never felt like I got back to 100 percent. I went from being able to jump over someone to having to go through them. But I guess it goes back to that desire to win. Just being given the opportunity to play again, that was enough motivation for me.

–––

Rejoining their teammates in time for the ’93 preseason, Engram, Mazyck, and Milne were walking examples of the power of perseverance.

ENGRAM: Some guys were more aware of it than others, but we all knew that there were guys who had dealt with some things. I think it drew us closer. It gave us that resilient spirit we had as a team.

MAZYCK: Joe always had this thing where you had to be tougher than tough, that you’re only as tough as the weakest link in the chain. Seeing what everyone was going through kind of brought together the different cliques and made us one unit. We had a common goal. We wanted to play for each other.

Chapter 4: Almost Famous

“We wanted to play for each other.” The disappointment of the ’92 season left a mark on the returning Lions, who believed they had the potential for greatness. Not content to let their coaches coax it out of them, the players—including those ’90 and ’91 recruits, many of whom were maturing into leadership roles on and off the field—decided to take the lead.

BRADY: Our winter workouts in ’93, it was a different attitude. We decided we were going to do things the way the old man told us to, embrace the coaches’ philosophies, and work really hard, but at the same time we’re going to have fun along the way. In the process, we realized those things don’t have to be mutually exclusive. A lot of those coaches had been on the staff in ’82 and ’86—they knew what it took, and they knew how much fun it could be.

KIRK DIEHL: I remember ’93 was the first year that a lot of guys chose to stay up here for the summer and work out. That was kind of unheard of.

ATKINS: Everybody stuck around, working hard. That was key. It would’ve been easy to say, “I just want to go home, relax a little bit.” But that wasn’t the case. The weight and conditioning program wasn’t mandatory, but everybody just bought in.

ENGRAM: That was a great summer. We’d be on the field, no coaches out there—it was about the team. It felt like a real family.

KILLENS: It was almost like a new beginning for us. That’s when a lot of the guys from the class of ’91 were becoming full-time starters.

ATKINS: In ’92, my sophomore year, a lot of us started getting more playing time and contributing. Once we were into our junior year, we had a lot of great ballplayers with a lot of experience.

BRADY: It was a combination of the seniors—guys like Lou Benfatti, Eric Ravotti, Tyoka Jackson—and the coming of age of some of the younger guys. The older guys were going to lead, and the younger guys were going to be accountable. It’s still a meritocracy. Some of those younger guys, based on the things they were doing on the field and in the weight room, were earning their voice.

–––

As the ’93 season approached, it wasn’t yet clear which voice would be leading the offensive huddle. Finally, on the eve of the season opener, Paterno named John Sacca the starter over Collins and talented sophomore Wally Richardson. But Sacca struggled and was replaced by Collins early in the Lions’ third game, a 31-0 win at Iowa; Sacca would transfer not long after. Meanwhile, at tailback, Paterno went with a three-man platoon, as fans and coaches alike waited to see which of that talented trio would emerge as the No. 1 back.

PITTS: That season was kind of a vetting process—who would emerge between John and Kerry, and we didn’t have a starting tailback yet. It was just seeing where everyone was going to fall. It was a young team.

CRAIG CIRBUS: At quarterback, Coach Paterno had a giant decision. To Kerry’s credit, he just persevered. He just kept working hard.

FORBES: We had the quarterback question. It was Kerry, Sacca, Kerry, Sacca. And then Kerry came into his own.

CONLIN: Kerry and John in ’93, that was a fiasco. With John leaving, then it was settled who our quarterback was.

PITTS: I was the starting tailback the first game.

CARTER: Coach Paterno came up to me before the Iowa game and said, “You’re going to be the starter.” I said, OK. When Pitts was starting those first two games, I was supportive. We were always supporting each other.

–––

Penn State went into its inaugural Big Ten season with a veteran defense expected to prop up a largely unproven offense. That’s roughly how things played out: The Lions started 5-0 for the second straight season before dropping back-to-back games to Michigan and Ohio State. The home loss to the Wolverines was memorable for a late, four-down goal-line stand by the visitors; two weeks later in Columbus, the Lions were dominated by the Buckeyes.

CIRBUS: As a staff, our mentality was always different at Penn State. You grew up watching Ohio State and Michigan playing for the Big Ten championship every year. That never occurred to us.

CONLIN: We were all fired up. The ’91 class, we were the first class recruited knowing that we were going into the Big Ten. We wanted to see how we matched up. It was big boys vs. big boys. And it was awesome.

KILLENS: We opened at home against Minnesota, and we got off to a real quick start. You could kind of see what we had.

GREELEY: We started to get that feeling back. We went into the Big Ten and started to play well.

BRADY: We have a chance to win the Big Ten. Had it not been for that Michigan goal-line stand, we’re Big Ten champions our first year in the league.

FORBES: One or two plays in that Michigan game change the season completely.

CONLIN: That was a horrible loss.

HARTINGS: We beat ourselves against Michigan. The only team that really beat us was Ohio State.

COLLINS: We took a pretty good beat-down at Ohio State.

CONLIN: Ohio State beat the crap out of us. That was a damn good team.

CARTER: Me being from Ohio, that’s Buckeye country—I got so much flack for leaving. So I grew up hating Michigan, and then when we went to Ohio State, I wanted to show out for my hometown. When we lost those two, it left a sour taste in my mouth. It was really hard for me. I cried after the Ohio State game. I wanted to beat them so bad.

DIEHL: Joe gave this speech after the game in the locker room. He said, “I’m tired of losing games like this. We’re going to show people what Penn State football’s all about. I don’t care if we win by one point, but we’re never going to lose again.” I’ll never forget that: “We’re not going to lose again.”

–––

They didn’t. The Lions finished Big Ten play with four straight victories, the last a 38-37 win at Michigan State that saw them rally from a 20-point second-half deficit. A high-profile bowl match-up with an SEC power beckoned, but even before then, they had made a point—to each other, if not yet to the rest of the nation.

STEWART: We were hoping to go undefeated, but we didn’t give up. The seniors didn’t give up, and we fought for them.

ATKINS: We lost to a couple of good teams, but that season gave us the confidence to know we could do some things.

FORBES: If you take the season as a whole, we beat up on a lot of teams. We played some really good football.

COLLINS: You could sense it coming together toward the end of the season. Especially the Michigan State game—it was kind of a shootout. We had to find a way to win, in a tough place to play, and we made big plays.

BRETT CONWAY: That last game at Michigan State, Kerry had one of his breakout games. We had to come back and beat them, and that was probably the game Kerry started really making his mark. You saw glimpses of what the future held.

GREELEY: We were in essence a yard away from winning the Big Ten our first year in the conference, and we realized a lot of the key contributors on that team were coming back.

KILLENS: We really had a good nucleus.

BRADY: I think we started to see the composure the team was going to display. It was all in the process of developing.

CONWAY: Going into that next season, all the potential was there.

–––

Part 2: A New Year’s Day battle with Tennessee foreshadows greatness; after an intensely focused preseason buildup, the ’94 season starts with a bang; and a diverse cast of characters unite to form one of the most dominant offensive lines in school history.

For more on the The Football Letter, including online archives (requires Alumni Association member log-in), click here.

Not yet an Alumni Association member? Click here.

Great article. Great!

Thanks, Sam.

Pingback: Hot Reads: Up Next | Hail Varsity

Pingback: The Football Letter Blog | The Legends of ’94

Pingback: The Football Letter Blog | The Legends of ’94

As a Nebraska fan, it would have been great to have seen PSU and Nebraska be able to tee it up that year. That was a terrific PSU team that deserved to play for the title. While you can make all kinds of arguments why PSU or Nebraska was the more deserving team, the proof would have been in the game itself.

By the way – many Nebraska fans are bummed that we aren’t playing a cross-divisional rival game with PSU going forward as a result of expansion. Truly going to miss that, it was such a great opportunity to build something between the programs.

Absolutely. Had the potential to be one of the all-time great 1-2 matchups. The guys from the ’94 team weigh in on this in the final installment of the series, up Friday.

Pingback: The Football Letter Blog | The Legends of ’94

Pingback: The Football Letter Blog | The Legends of ’94

Pingback: The Football Letter Blog | Legends of ’94: The Oral History

very nice